Credentialing

Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE)

An Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE Exam) is an assessment designed to measure performance of tasks, typically medical, in a high-fidelity way. It is more a test of skill than knowledge. For example, I used to

NCCA Accreditation of Certification Programs

NCCA accreditation is a stamp of approval on the quality of a certification program, governed by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA).™ This is part of the Institute for Credentialing Excellence™, the leader in

What is the Beuk Compromise?

The Beuk Compromise or Beuk Adjustment is a method for a “reality check” on the results of a modified-Angoff standard setting study. It is well-known that experts will often overestimate examinee capabilities and choose a

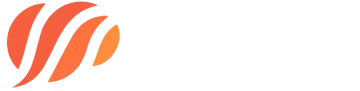

Test Score Equating and Linking

Test equating refers to the issue of defensibly translating scores from one test form to another. That is, if you have an exam where half of students see one set of items while the other

The Bookmark Method of Standard Setting

The Bookmark Method of standard setting (Lewis, Mitzel, & Green, 1996) is a scientifically-based approach to setting cutscores on an examination. It allows stakeholders of an assessment to make decisions and classifications about examinees that

What is a Standard Setting Study?

A standard setting study is a formal process for establishing a performance standard. In the assessment world, there are actually two uses of the word standard - the other one refers to...

What is Item Banking? What are Item Banks?

Item banking refers to the purposeful creation of a database of assessment items to serve as a central repository of all test content, improving efficiency and quality. The term item refers to what many call

Ways the Word “Standard” is used in Assessment

If you have worked in the field of assessment and psychometrics, you have undoubtedly encountered the word “standard.” While a relatively simple word, it has the potential to be confusing because it is used in

Subject Matter Experts (SME) in Exam Development

Subject matter experts (SME) are an important part of the process in developing a defensible exam, especially in the world of credentialing and certification. A SME is someone with deep expertise on the content of

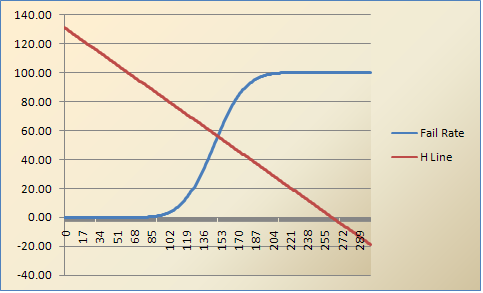

What is the Hofstee method for setting cutscores?

Have you heard about standard setting approaches such as the Hofstee method, or perhaps the Angoff, Ebel, Nedelsky, or Bookmark methods? There are certainly various ways to set a defensible cutscore or a professional credentialing

What is decision consistency?

If you are involved with certification testing and are accredited by the National Commission of Certifying Agencies (NCCA), you have come across the term decision consistency. NCCA requires you to submit a report of 11